Cherokee

The novel’s main protagonist, Sequoyah, is four years old and an orphan. When his aunts grow tired of raising him, the strange, telepathic boy is placed in an Indian orphan school that successfully erases his Cherokee identity. By the time he graduates in 1959 and enters college, he’s a thoroughly messed-up young man. Denying his name, he calls himself Ariel. He begins a tough journey of self-rediscovery that takes him to terrifying, and sometimes amazing, places. Along the way, odd pieces of his heritage come back.

Carlisle Indian Industrial School students, photo, 1879. John N. Choate of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ariel’s school was less dehumanizing than most, but nonetheless it destroyed his youthful spirit. One of the most notorious schools that served as a model for similar institutions across the U.S. was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, designed to “Kill the Indian—save the man.” Such schools were established after the Civil War and lasted almost to the end of the 20th century. Claiming to be humanitarian, this broad program by government and charitable organizations was inherently racist in breaking families apart and erasing culture. The boys and girls were “Americanized” and prohibited from using their native languages and customs.

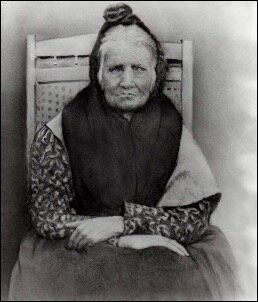

Elizabeth Brown Stephens, a Cherokee who walked the Trail of Tears. She was eighty-two when this 1903 photo was taken. Lmaotru, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

During an out-of-body experience, Ariel finds himself on the Trail of Tears in 1838 in the stifling heat of summer during one of the early Cherokee marches. The devastating relocation of the Cherokees to Oklahoma in seventeen detachments was one part of a massive displacement forced by the United States government on approximately 60,000 Native Americans from the South between 1830 and 1850. Many thousands died on the way or soon after arriving. The Cherokee removal was the last Southern relocation, hastened by the discovery of gold in 1828 in Georgia. Treaties were scrapped along with land ownership rights in a land-and-resources grab unprecedented in its relentlessness.

The Last Shade Tree contains transliterated Cherokee words and a few complete sentences that are vital to the story.* Even though Ariel’s Indian orphan school robbed him of the only language he knew—Tsalagi, or Cherokee—he doesn’t entirely forget his childhood tongue that he recalls partially in adulthood. Before her death, Ariel’s mother named him after the very famous Sequoyah who single-handedly invented a system of writing using the syllable sounds of spoken Cherokee. Her choice was prescient because Ariel eventually realized his immense poetic gift.

19th-century print of a painting by Charles Bird King (1785-1862)

Sequoyah (c. 1770 - c. 1843), a non-literate Cherokee originally from Tennessee, completed the syllabary in 1821 after much trial and error. In 1825, the Cherokee Nation officially adopted the ingenious method to teach the reading and writing of its oral language. The result was electrifying: the literacy rate among the Cherokee quickly surpassed that of the American settlers of the region. Soon the laws of the Cherokee Nation and the first newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, appeared in print.

The beautifully conceived Cherokee syllabary remains almost unchanged since its completion. Some of the eighty-five characters that represent syllables look like Latin, Greek, or Cyrillic letters, but are unrelated in sound. The vowel sounds “a,” “e,” “i,” “o,” and ”u” are placed across the top of the chart. An additional vowel is added, a “v” that has a soft “u” sound as in “sun.” Sequoyah’s daughter Svnoyi’s name would be pronounced in three syllables: “Su-no-ye.” Still vital today, the Tsalagi syllabary may be found among the thirty-plus writing systems installed on the iPhone.

_______________

*Cherokee language expert Harry Oosahwee, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and a retired professor at Northeastern State University in Oklahoma, kindly corrected my attempts at choosing the idiomatic words in Tsalagi and doing the transliterations.